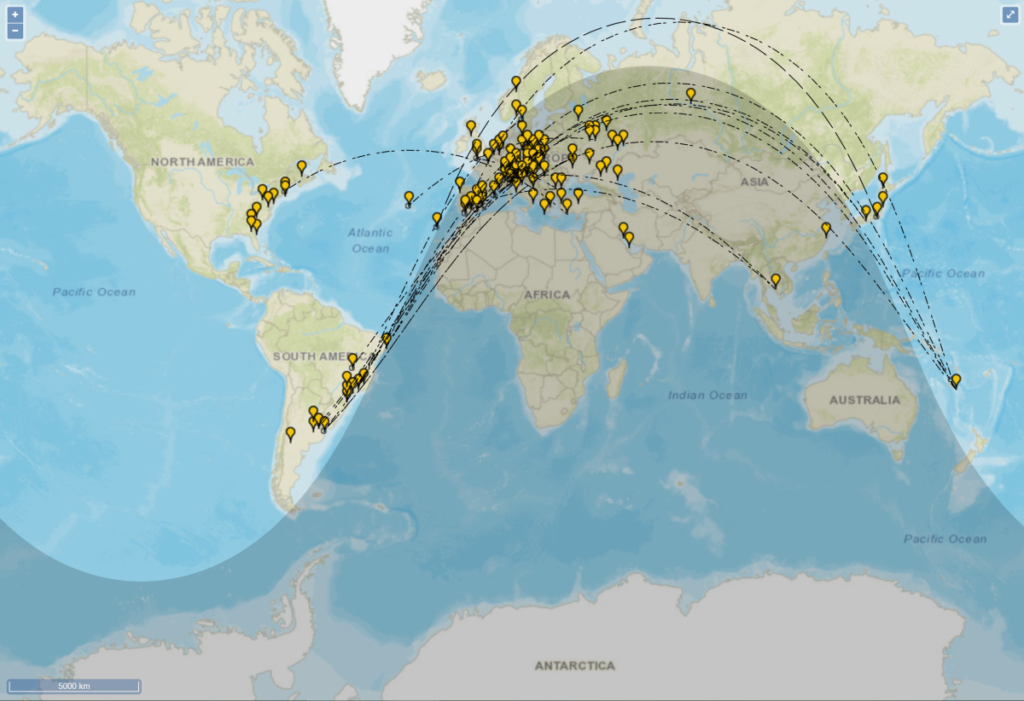

In the image below, created yesterday evening, you can beautifully see the effect of what is called the ‘gray line‘ (see explanation by Paul NA5N Harden below). It is the line between day and night, as can be seen in the image. Along this line radio connections are ‘propagated‘ by layers in the ionosphere.

The gray line

During the day, solar radiation collides with the molecules in our ionosphere, ripping off electrons. These electrons are called “free electrons” because they are not attached to an atom or molecule. All of these free electrons cause the density of the ionosphere to increase. The more dense the ionosphere, the higher the frequency that is reflected back to earth. This electron density is what determines the maximum usable frequency (MUF), and the action of solar radiation separating electrons from the molecules is called ionization.

During the day, solar radiation causes ionization to stratify, that is, to form distinct layers. The layer closest to the earth is called the D-Layer. It does not reflect signals generally, but does absorb some of the energy, and hence the D-Layer is often called the “absorption layer.” Higher up in our ionosphere, we find the E- and F-Layers. These layers do reflect the signals back to earth if they are below the MUF, and is exactly what causes “skip propagation.” So during the day, the sun is ionizing the D, E and F layers (there are actually two F layers, called F1 and F2). Your 10m signal must travel through the D-Layer, getting attenuated, then bounces back from the E or F layer to some exotic DX spot, passing through the D-Layer for more absorption again. But since solar radiation has to travel the farthest to get the D-Layer, absorption is usually fairly minimal. So far, during the middle of the day, we have moderate absorption, and good skip propagation.

AT SUNDOWN … solar radiation no longer strikes our ionosphere right above our heads, and ionization stops. This means there is no solar radiation to form free electrons. In fact, without this solar radiation, these free electrons tend to get attracted back to recombine with their host molecules. This is called “recombination” (gee, how original!). Recombination, when it starts to get dark, causes the electron density to go down, forcing the MUF to go down as well, which is why by total darkness, 10m (and a bit later 15m) are completely dead. The MUF is far below 28 MHz.

The D-Layer is the first layer where ionization stops, since the sunlight no longer reaches near the surface of the earth, but is still illuminating (and ionizing) the ionosphere far above our heads. (For the same reason, we can see satellites pass overhead in the early evening … it’s dark on the ground, but the satellites are still being illuminated.) As the D-Layer goes into recombination, the electron density goes down, and the absorption does down. This is why signals appear stronger at night, because there is less absorption by the D-Layer at night.

BUT DURING TWILIGHT … OR IN THE “GRAY LINE” … the D-Layer suddenly causes little absorption to signals passing through it, while the E and F layers are still being ionized by sunlight. This makes for about 45-60 minutes of interesting operating, especially for QRPers (low power operators). There is almost no signal attenuation, but the MUF is still very high, so long-distance skip is still possible. However, when the sun quits illuminating the E and F layers, the MUF can drop dramatically … sometimes with only a few minutes of warning, sometimes between heartbeats. So when you establish a contact, get the QSL info fast!

One other advantage of gray-line DX is that your signals tend to reflect off the edge of the ionized portion of the upper layers. This means propagation will often be in a southerly direction, bouncing along the shadow, or terminator, between sunlight and darkness.

Nort America centric

This is good for working into South America and the South Pacific. Your signals can also bounce northward along the terminator, bending around the pole, and down the morning terminator across eastern Europe, the Middle East, and into Africa (depending on the time of year).

Northern Europe centric

In Europe the morning gray line gets us in contact with the Middle East and Africa, where the evening gray line gets us to South America, Asia and the Australian region.

So gray-line DX also affords an opportunity to work portions of the world not usually accessible during the day, where propagation tends to be more east-west circuits.

The same principles apply at sunrise. The upper ionosphere begins to become ionized, while the D-Layer is still dark and offers low absorption, although, the MUF in the morning generally does not support propagation on 10m, so most people enjoy gray-line work on 20m or 15m (if open). Morning gray line can even be eventful on 80m and 40m, due to the low absorption before the sun starts heating the D-Layer.

And remember, 10m and 15m (and often down to 30m) are not generally bothered by a geomagnetic storm. So even during major geomagnetic storms, the higher bands may be open and fairly quiet. And even if a bit noisy, the short period of gray-line operating can still produce a couple of good QSO’s.

Hope this helps to explain the “gray line” phenomenon, and hope it helps you snag a few new ones.

By Paul Harden (NA5N), National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Socorro, New Mexico

Reprinted without explicit permission on the assumption that Paul is OK with the idea or he wouldn’t have posted it to the Internet, and there’s no copyright notice.